[This is a deeper dive into one of the author’s stories found in “How A Man Not Named Dan Came to Own Dan’s Cafe for Six Decades,: published June 10th in the Washington City Paper. For the first of these deeper dives, click here. For more details about Dan’s Cafe and Dickie DIckens (including pictures) click here.]

In spring 1941, as World War II raged, in a raid referred to as “Operation Berlin,” two German battleships sank or captured nearly two dozen merchant ships in the Atlantic Ocean. One sunken ship, a British-flagged steam ship called the SS Silver Fir, had transported cargo around the world as a tramp steamer for 16 years before its destruction on March 16, 1941. One member of the ship’s crew perished, while the rest were captured by the Germans.

A decade earlier, this same ship embarked from the British colony of Singapore in Southeast Asia, eventually making a stop in New York City. Joining the ship in Singapore was a 21 year old man named Bee Lee (official U.S. government records say he was born in 1909 but are not consistent on the date, stating either February 29-a date that does exist-or March 29. In all likelihood, neither is accurate) in Fuzhow in southeastern China. Despite the nearly 50-year old Chinese Exclusion Act, which virtually banned immigration to and naturalization in the U.S. for anyone in the world who was of Chinese descent, Lee entered the United States on January 30, 1931, soon changing his name to Amoy George Dan.

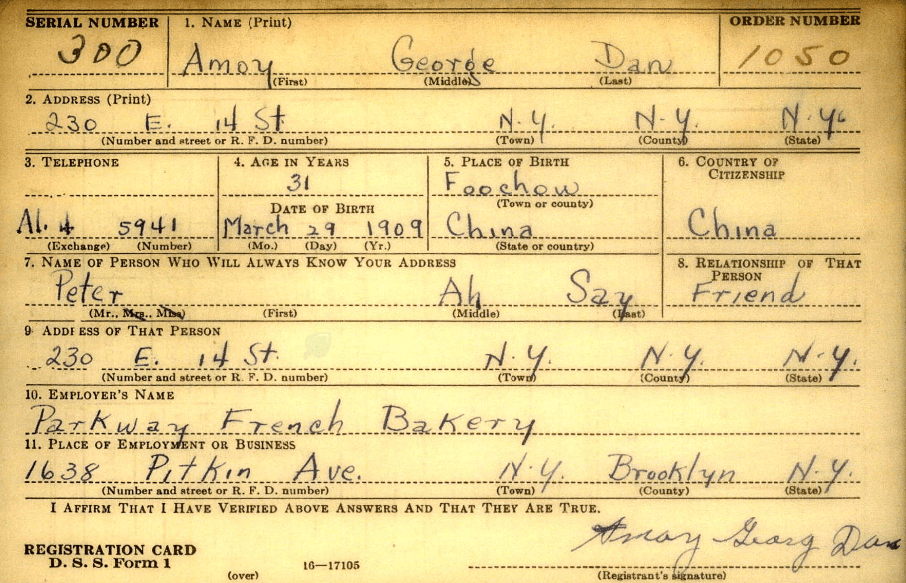

Dan settled in Manhattan, and by 1940, he was living with three other Chinese men in an East Village apartment (Census records refer to him as the head of household), working as a counter cashier at the Parkway French Bakery across the river in Brooklyn.

As WWII ensnared the United States, Dan, like all other adult men in the United States under the age 65, regardless of citizenship or immigration status, was required to register for the draft. On April 13, 1943, Dan’s number was called, and he was drafted into the Army Enlisted Reserve Corps, reporting for active duty the following week. One of the estimated 20,000 Chinese-Americans who were part of the U.S. armed forces during WWII, Dan served a year and a half stateside until his honorable discharge in October 1944. An estimated 1 in 5 Chinese-American adult men served; 40% of them, like Dan, were not U.S. citizens.

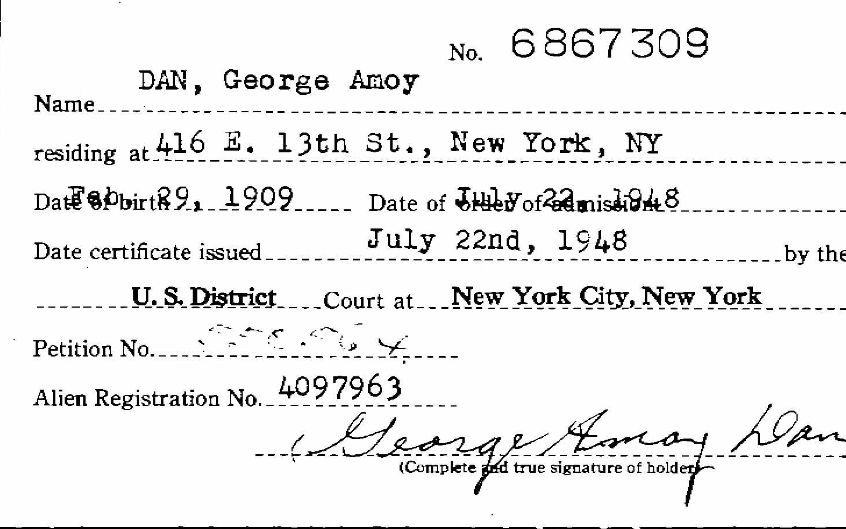

The legal fortune of Chinese-Americans like Dan changed quickly once the U.S. entered the war, as Japanese attacks on China led to the latter becoming an ally of the United States. Soon, government funded media campaigns encouraged favorable views of Chinese (as opposed to Japanese), even including attempts to help Americans identify the differences between them. In fact, unlike other Asian Americans conscripted, most (an estimated 75%) Chinese-Americans served in non-segregated units alongside whites. In December 1943, owing to the favorable opinion toward allies like China, Congress finally repealed the Chinese Exclusion Act. After six decades, those of Chinese descent could again become naturalized U.S. citizens, and coupled with other new laws, WWII veterans, even those who couldn’t prove lawful entry, could have an expedited route to citizenship. Dan barely made the deadline, petitioning for naturalization with five days to spare, on December 26, 1946. In his petition, he listed his occupation as “saladman,” standing 5’6 and weighing 140 pounds, while two other Chinese-Americans (including one roommate) attested to his good standing. He also asked that his first and middle names that he took when arrived in the U.S. fifteen years before to be switched officially. The petition was granted, and George Amoy Dan took the oath of allegiance as a naturalized U.S. citizen on July 22, 1948.

Dan’s wife Lee Joe née Pan (born in 1913 in Fukien Fooch, Taiwan) joined him in the United States following his naturalization, arriving in the country on October 8, 1949 on a Phillipine Air Lines flight in San Francisco from Hong Kong. She was one of many Chinese women who emigrated to the U.S. in the late 1940s; the severe restrictions of the Chinese Exclusion Act meant that virtually all who immigrated from China in the previous six decades were single men.

In March 1956, drawn by new opportunities south, George and Lee Joe Dan purchased a house their family (they had at least 2 children – Helen and Jimmy) moved into at 1647 Fuller Street NW in Washington, D.C., not far from the present-day Line Hotel.

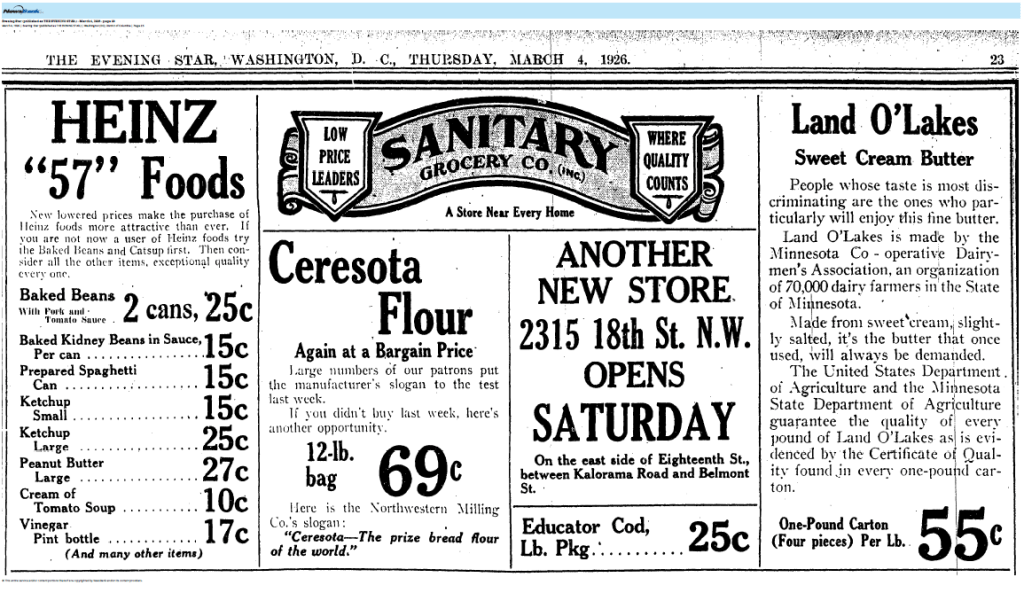

The Dans soon took over a restaurant in the neighborhood at 2315 18th St. NW, most recently Suber’s Restaurant, the site of tragic killing by the proprietor John Suber of 24 year old Army veteran Charles Henry Watson (read more here). The building at this address was a 1,200-square foot, one-floor structure, the creation of the first owner Cesar Casanova, designed by M.T. Vaughn and built in 1911 by Howard Etchison and his team, a couple decades after the area was first developed as “Washington Heights” subdivision. Its first life was a grocery store, operating as a series of small neighborhood grocer for nearly three decades: Elphonzo Young’s, John Kracke’s, Mid-City Market, Central Market, and starting in 1926, part of the Sanitary Grocery chain.

This chain still exists in DC under a different more well known name – Safeway, which bought Sanitary Grocery in 1928 to establish an east coast presence before phasing out the brand completely in 1941. Sanitary Grocery operated in this location for 13 years, serving the neighborhood, then commonly referred to as “18th and Columbia” that had emerged as one of DC’s most “fashionable” and “high-grade” neighborhoods, as evidenced by the presence of DC’s most preeminent fur coat shop, and multiple grand theaters. A 1938 newspaper report of a overnight burglary of 18 pounds of cooked ham, 35 cartons of cigarettes, 4 boxes of chewing gum, and a case of ginger ale gives an idea of the wares sold to these neighboring residents.

By December 1939, however, the building’s life as a grocery had ended, and the owner leased it for the first time as a restaurant, and so the place has been the site of hospitality for 85 years now. Owners/operators of eateries or the building before the Dans took over included Mary Gustafson, Hassan Amin, Roxie Shannon, and the Subers. At some point during this time the building even featured a skylight – in one night in July 1942 burglar entered through one and took $28.65 ($565 in 2025 dollars) from the cash register.

By the time the Dans had taken over, the neighborhood no longer possessed its lofty reputation. In fact, just months before the family moved to the area, in December 1955, the two principals of the newly integrated neighborhood schools (Adams and Morgan) spearheaded the creation of an integrated grass-roots organization comprised of community groups and members, called the Adams-Morgan Better Neighborhood Conference, which expressly aimed at stemming the deterioration of the neighborhood and preserving it as a racially balanced, middle class area. The neighborhood today owes its name to the creation of this conference and the efforts to revitalize the area that followed.

After Dan’s Cafe opened in 1956, George served as the manager and Lee Joe served as assistant manager, and it was patronized primarily (or exculsively) a Black clientele – at the time DC restaurant spaces that did so were sometimes marketed specifically as being “ideal for Chinese.” In June 1960, the Dans bought the building from the widowed Bessie Suber for $6,700 (including $3,000 down payment with the rest covered by monthly $40 payments) (in 2025 dollars, roughly $73,000 total, with $33,000 down payment and $436/month). News reports mention wallets stolen from Dan’s in July 1956 and February 1960. In December 1964, another deadly shooting happened at the location when Flody Daniels was shot in the chest while in the men’s restroom by 41 year old Bloomingdale resident Joseph Perry after an alcohol-fueled quarrel.

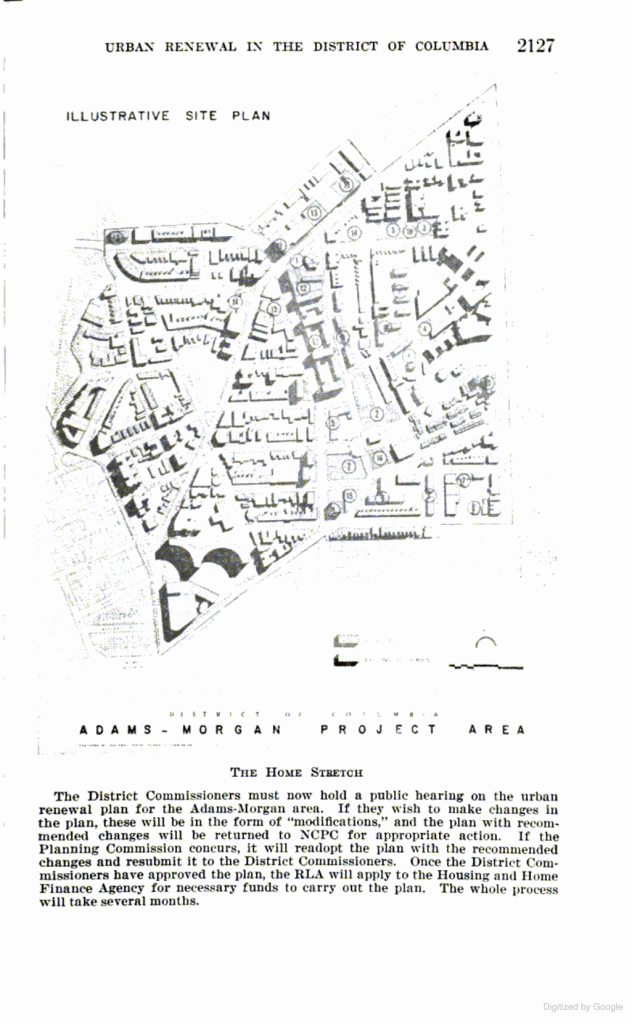

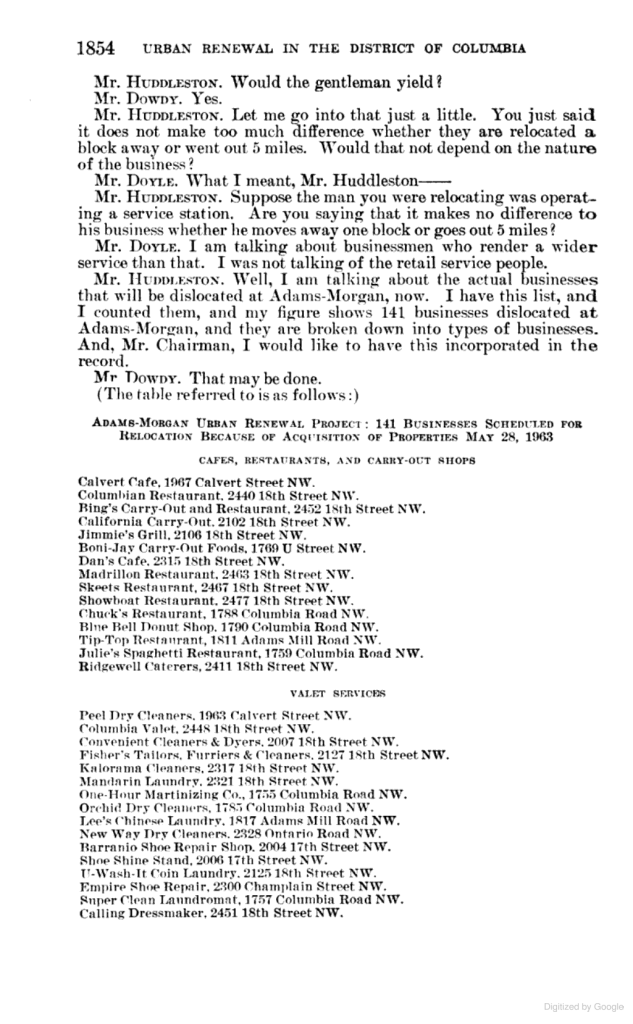

In the meantime, efforts to revitalize the neighborhood continued. The Adams-Morgan Better Neighborhood Conference worked with staff and students from the American University, aided by an $8,000 grant ($90,000 in 2025 dollars) from Sears Roebuck, to conduct a demonstration project in the late 1950s to help improve the neighborhood. This morphed into the Adams-Morgan Planning Project, a more ambitious urban renewal plan conducted by the Federal/DC government that would include demolition of existing properties. One area slated for demolition under this plan was nearly the entire east side of 18th Street NW south of Columbia Nw including the building housing Dan’s Cafe. Planners felt the businesses here were mostly “marginal” ones in substandard structures that at best provided a low level of wages for the business owner. The plan was to build in its place a large, tall residential building with ground floor retail and extensive underground parking. Perhaps welcome at the potential payouts from the Government that would result from demolition, it does not appear that many building and business owners affected objected. In the meantime, the new term for the neighborhood began to stick, as real estate ads advertise “Adams-Morgan” locations starting in 1960.

But after a decision was made to exclude the nearly all White, less economically distressed area west of Columbia Road (often identified as Kalorama Triangle today) from the planning project, as well as due to objections from some residents and business owners who had seen how Southwest was basically obliterated due to an earlier urban renewal project, in February 1965, the National Planning Commission overruled their own staff and killed the project, saying it was not in the “public interest.” Adams Morgan that we know and love today would be quite different if this had gone through.

Five months later, the Dans transferred ownership of Dan’s Cafe to Clinnie “Dickie” Dickens, who continued the own the bar until he died in February 2025 (his sons now run it).

It’s not clear what led Dan to turning over Dan’s – perhaps the failure of the Adams-Morgan urban renewal project that would have torn down his building (and the resulting financial compensation) had something to do with it. Dickens provided additional context to me: Dan’s extended family members (whether by blood or close affiliation – around the same time other DC restaurants were owned by others with the last name of Dan: Chong, Susie, Sam, Eleanor Witherspoon, Susan Mei, Mee Hueng, Da Shing) who also moved down to DC would all follow this general path: 1) start businesses, 2) pool profits together and 3) purchase homes back in New York City where, one-by-one, 4) families would return to live. This may have occured in connection with the transfer of Dan’s to Dickie, though the timeline is a bit hazy. Reportedly, Lee Joe and the Dan children moved to Queens, New York while George Dan continued to run a similar tavern with a Black customer base in what today is known as Shaw. George Dan was running this spot, called New Republic Café (1217 7th St. NW at corner of 7th and N St. NW), as early as May 1958; an advertisement the previous year from the former owner describes it as a “beer, wine tavern” with a “great colored trade” highlighting that it would be “ideal for Chinese.” The establishment survived the 1968 riots that occurred after the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. that decimated the neighborhood, but in 1971 DC purchased the property and demolished it, along with the rest of the block, to build public housing. Dickens said George Dan then returned to join the rest of his family in the Flushing area of Queens. The iconic 14-seat wooden bar at Dan’s Cafe that remains today, with recessed cup holders and cracked tile was in fact originally installed in the New Republic Cafe before it closed and George Dan moved it to it current location.

The Dans sold their Fuller Street house in June 1979, just 6 months before George Dan died at the age of 70 in December 1979. Lee Joe out-lived her husband for more than two decades, passing away in October 2002. To this day, the iconic building that houses Dan’s Cafe remains in the family’s hands after being transferred in 2004 to Geleda LLC (apparently named after the original owners: GEorge LEe DAn), a company controlled by the Dans’ daughter Helen Dan, who still lives in Queens.

Leave a reply to Anonymous Cancel reply